When Scenic Design Becomes a Puzzle

by Justin Hooper

Okay, here’s a little fact that I have never before admitted—I don’t consider myself to be a much of an artist. Most scenic designers that I know grew up sketching and painting. In school, they excelled in classes related to the arts. They are the individuals who utilize the artistic right side of the brain. I have always desired to be one of these people. I am not one of these people. I’m just really good at faking it.

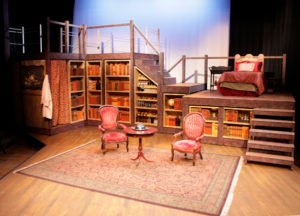

I’m a math guy. I like numbers. They are concrete. Understandable. And I LOVE puzzles. When I read a new script. I look at it as a puzzle. There are a lot of factors that must be considered in order to create a successful scenic design and I find it easiest to begin by stripping them down to their simpler, more understandable numerical form. How many doorways are referenced in the script? How many windows? At most, how many people will need to be sitting on furniture at any given time? I create a sort of equation of all the items necessary to allow for the written action of the play. Over the years, I have gotten pretty good at finessing this equation. Distance between doorways, for example, can sometimes be very important, especially within a farce. If specific comedic timing is required for a character to enter, take a certain amount of steps while speaking a line in a particular rhythm, and then exit through a different doorway, this information must be taken into account. I often have to try walking these traffic patterns out myself, script in hand, in order to be comfortable enough to propose the spacing to a director. The flies on the wall in my scenic studio get a unique one-man show each time I find myself designing a farce. (Please come see Commonweal’s upcoming production of Boeing Boeing to see if I get the math right!)

Only when I have an idea of what the play requires structurally do I begin to take the “art” of the show into account. This is where I really begin faking it. I am fortunate enough to have perfectly timed the beginning of my design career to the beginning of the accessible internet. A little trade secret—if you are creating a design for It’s a Wonderful Life, Radio Play, for example, it is quite simple to google “Art Deco, New York, Radio Station” and pick architectural details which you find personally appealing and easy enough to build within your scheduling and budgetary restrictions. I try my best to link many of the artistic decisions I make to subtext within the script (create little Easter eggs, if you will) but I will certainly admit that I often end up merely proposing things that I think would be personally rewarding for me to build. After all, I like building things. I’m a math guy.

At this point, I meet with the director and try my best to use artistic terminology to describe my choices. He or she then volleys back a myriad of questions and suggestions and I return to the drawing board to rework my equation. This may sound like a negative aspect of my job—I assume that people who don’t work in an artistic field would loathe a situation in which they had just completed multiple days of work only to have their boss hand their work back to them with another several days’ worth of edits—but this is actually the part of the job that I appreciate most. It is this part that allows a left-brained math-loving guy like me to fulfill his artistic dreams.

Theatre is a collaborative art. Dozens of people work together to create the final product of the show itself. A scenic design is not a stand-alone art piece. It is a vehicle used to supplement the story of a play and it’s desired effect; whether that be to move an audience to tears, provoke deep thought on a subject, or to simply give them a fun night out on the town. On any given project, I find it best to use my fellow artists as a crutch; a sounding-board for my artistic ideas. I then try my best to incorporate their suggestions. I am humble enough to understand that I don’t always know what is best for the art of the show. The best collaborators are the ones who listen to criticism and adapt. The goal is to create a final product that is cohesive and everyone on the team can be proud of. In my experience, the audience usually agrees.

Justin expertly designed the last three productions of the 2018 season and will be back for more in 2019. We enjoy Justin’s work quite a bit around the CWL and hope that you all do, too.

To see Justin’s current work on the CWL stage, get your tickets today for

It’s a Wonderful Life: A Live Radio Play playing through December 22.

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you at the theatre—Jeremy.

I enjoyed reading this ‘behind the scenes look” Justin. Your passion for your work shines thru! I look forward to seeing the sets in 2019!

Thanks for the comment, Martha and for your strong support of the work of the CWL. Happy Holidays and we will look forward to welcoming you back in 2019.